His wage

would be $1.00 per day with a 10 cent increase when overseas.

Archibald’s

first child Ellen was born in Pincher Creek the 13th February 1915 just twelve

days after he had enlisted

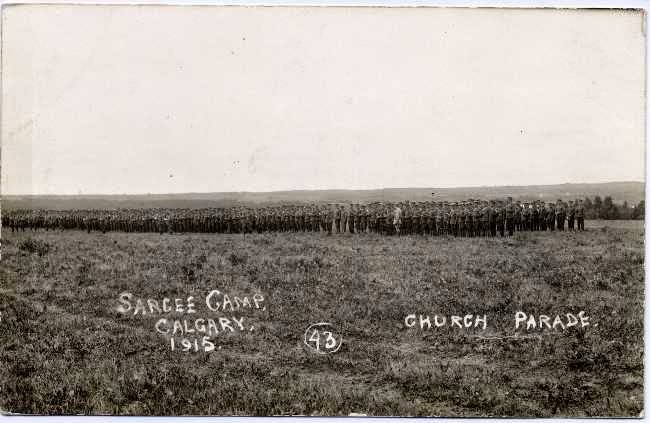

SARCEE CAMP CALGARY ALBERTA 1915

When WWI

broke out a new site for a training area was selected north of the Elbow River

named Sarcee Camp, near Calgary. Work started on the camp in April of 1915 and by summer the area

was suitable for housing and training, it was designed to accommodate 6000.Sarcee Camp

was a tented city with several wooden buildings for administration staff and

supply services. Roads were constructed and the camp was serviced with running

water, electricity and a street car service. The 13th

C.M.R. along with the 12th C.M.R.and three battalions of infantry

were the first units stationed there when it opened.

In the camp

companies were arranged in avenues that were bordered by rows of tents; Large

whitewashed stones were used to outline the various sections.

A normal day

started at 4:00am with exercise on the parade square, after which breakfast

consisting of oatmeal, bacon, potatoes and coffee was served. Next there were

classes in physical training and rifle practise along with other necessary

training. After a noon break more activities continued until supper hour.

Evening were spent playing ball, writing letters or simply resting until lights

out at 9:30pm

Wednesday

was visitor’s day. Visitors were entertained by bands and military

demonstrations. Martial music was heard on all sides and soldiers were marching

everywhere.

On 25th

June 1915 Grandpa wrote to his wife Eliza, whom he refers to as Lizzie.

|

| Front of Post Card |

25 June 1915

Dear Lizzie the black

watch you gave me is not going very good, it has stopped 3 or 4 times since I

left and also I was out on parade today again & I am afraid I will need

to lay of with it again as it is pretty done since we came in today. I ain’t

going to give Bob Dick that 2 dollars for boots as I think I can get a pair

without. You loving husband Archie

The Sarcee

Camp closed for the winter and the 13th C.M.R. depot was relocated

to Medicine Hat, anticipating they would leave shortly overseas.

MEDICINE HAT ALBERTA 1915-1917

In the spring of 1916 it was thought Archibald

would be headed overseas shortly and his wife Eliza was expecting a baby in

June so it was decided she take their 14 month old daughter and sail overseas to

stay with her sister in Ilford, Essex so she would be close to him in England

when he arrived. Eliza and Ellen sailed from New York on 5th April 1916 for

England and arrived 15th April in Liverpool then took the train to Ilford, On 18th

June 1916 a son was born in Ilford.

A week before Archibald was given notice of his departure for England

In the mean

time the authorities decided to send no more mounted rifles overseas and it

became necessary to raise the 13th Canadian Mounted Rifles to

strength of a full infantry battalion. To obtain full infantry more recruiting

was necessary adding another 500 men to the 674 they already had. One of the notable features of 13 CMR was the 42 men born in Japan in its ranks. By the early part of 1916, there was a shortage of volunteers for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and the solutions included conscription and removal of impediments to enlisting what had earlier been considered undesirable nationalities. The appearance of not only Japanese, but also eastern Europeans born in countries on the Allied side, in the nominal rolls marked a decided change in recruiting policy.

Recruiting was done over time and by June of 1916 the 13th

Overseas Mounted Rifles, as it was now called, was ready to head east. On

Saturday the 24th of June 1916 the 13th O.M.R. left

Medicine Hat . Thousands of people on the platform bid farewell to 13th

O.M.R. Regiment and they departed in a downpour of rain and the band of the unit

played until the last moment.

The train took them east and they arrived in Halifax Nova Scotia in time to board the “S.S.Olympic” which sailed on 29 June 1916 with a roster of 34 officers and 933 other ranks.

A week

later, on the 6th July 1916

they arrived in Liverpool, England and from there another ride on the “Rattler”

to Shorncliffe Camp in Folkestone, Kent, where the Regiment was disbanded and

used to reinforce other units. Draftso Lord Strathcona’s Horse, Royal Canadian

Dragoons, Fort Garry Horse and to the Royal Canadian Regiment and Princess

Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Depot. The balance were absorbed by Canadian

Cavalry Depot on 19 July 1916 of which Grandpa was one. Due to the nature of warfare, cavalry units

would see little action.

After

arriving and once cleared from quarantine, the men were granted a short leave

and an opportunity to explore the surrounding towns and villages or travel to

London for a short visit. I’m sure Grandpa took this time to visit his wife,

daughter and new born son in Ilford only just north of the camp.

Being in Shorncliffe brought the men closer to the

action, they looked across the Channel to France and

wondered what was happening there, they could hear the boom-boom-boom of the

guns in Belgium. They knew that, only fifty or sixty miles away, men were

fighting and dying. Before this, the war had seemed very unreal, but the sound

of the guns made them realize that it was a grim reality.

The

newcomers proudly wore their uniforms and carried a full soldiers kit,

including two heavy army blankets, mess tin, a trenching shovel and a Ross

rifle complete with bayonet.

Their Canadian equipment

would be replaced by its superior British-made equivalent. “The tight fitting

Canadian tunics with stand-up collars gave way to the looser, more comfortable

and better made, British jackets. Commonly

considered to be made of brown paper, their Canadian-made boots disintegrated in

wet conditions and were also replaced.

As

a Farrier Sergeant, Grandpa was required to look after the regiment horses,

this included shoeing, tending to sick ones and putting down wounded or sick

ones. Because he belonged to the cavalry unit he saw little action in the

traditional role but did provide a valuable service.

Horses

played a major role , when war began in 1914 the British army possessed a

mere 25,000 horses.

The War Office was given the urgent task of sourcing half a million more to go

into battle. They were essential to pull heavy guns, to transport weapons and

supplies, to carry the wounded and dying to hospital and to mount cavalry

charges. A Farrier Sergeant would be in charge of them and help train them up.

From Shorncliffe they were transported to the port and hoisted onto ships

crossing the Channel before being initiated into the front line either as

beasts of burden or as cavalry horses. The supply of horses needed to be

constantly replenished and the main source was the United States, with the

British government arranging for half a million horses to be transported across

the Atlantic in horse convoys. Around 1,000 horses were sent from the United

States by ship every day. They were a constant target for German naval attack,

with some lost en route. The horses were so vital to the continuation of the

war effort that German saboteurs also attempted to poison them before they

embarked on the journey.

Horses were so vulnerable to

artillery and machine gun fire, and to harsh winter conditions in the front

line, that the losses were

high. The loss of horses greatly exceeds the loss of human life in

the battles of the Somme and Passchendaele.

Daily

routine at Shorncliffe consisted of revelle at 5:30 am with a daily march ,by

six thousand Canadians, to the beach for a bathe. Their day was

structured until lights out at around 10 pm. It incorporated physical drills,

parades, training and marches, punctuated with meal times.

In training ‘jam tin’ bomb were made by the

men from a real jam tin packed with explosives. To hone the soldiers’ aim, the

bombs were targeted at the recently dug trenches, much to the chagrin of the

men who had constructed them. However, a number of the trenches dug by

Canadians around Shorncliffe still survive to the present day.

The

‘Y’, as it was affectionately known, also ensured that there was always a

plentiful supply of notepaper and pencils for writing letters to family and

friends back home in Canada. Grandpa always claimed it was the “Y” that had

been the most helpful during his time overseas.

In 1917 the

wives of the Canadian soldiers were asked to return to Canada as there was a

food storage in England, and as Eliza Piper was now considered a Canadian, on

14th April 1917 Eliza and the two children left Liverpool, England aboard the

“Olympic” to arrive in Halifax on 20th April 1917. Eliza and the

children returned to Alberta by train and lived in Medicine Hat to wait for

Archibald’s return.

On Friday 25th May

1917, Shorncliffe, Folkestone and Hythe were hit by an air raid by German

aeroplanes. Eighteen soldiers, seventeen of them Canadians, were killed, with a

further ninety injured at Shorncliffe Camp. The early evening raid caught everyone

by surprise and caused the deaths of seventy-nine civilians, a high proportion

of whom were women and children.

London

had been the prime target for this bombing operation. However, because of thick

cloud as they approached the City, the aeroplanes turned south into Kent

instead. The inhabitants made no attempt to find cover, being familiar with

military sounds and distant explosions. No air raid warning had been

forthcoming and none of the towns had hooters or sirens in place.

FRANCE and BELGIUM OCT 1918-JAN 1919

Early

October 1918 Grandpa was confined to barracks and then on the 7th October 1918 marched the few miles to

Folkestone Harbour, laden with full kit necessary for survival in the field.

Leading down from ‘The Leas’ into the harbour, was a short road named ‘Church

Slope Road.

He would

soon see that his time at Shorncliffe could be compared to a ‘holiday camp’,

when set against the brutal conditions he would find in Flanders and France.

On 11 November 1918 an armistice was signed and all fighting stopped.

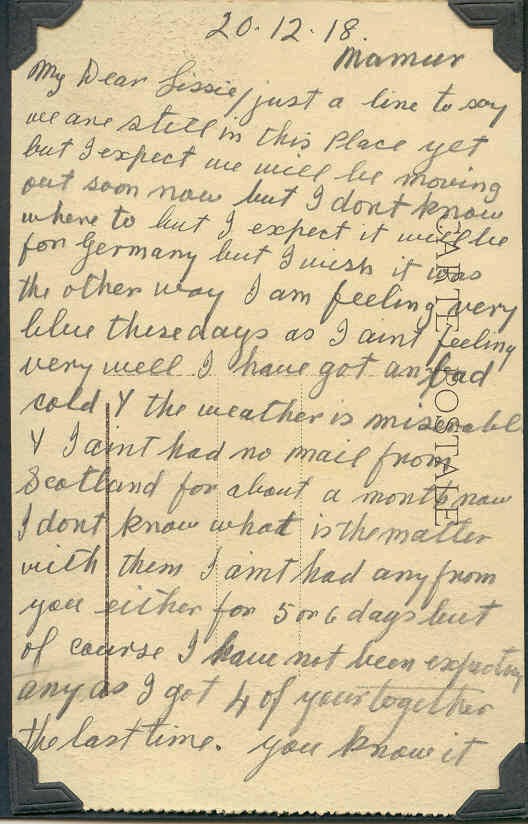

On the 20th of December 1918

Grandpa wrote a postcard to his wife in Canada. He was in Namur, Belgium. It

read

20.12.18

Namur

My Dear Lizzie, just a

line to say we are still in this place yet but I expect we will be moving out

soon now but I don’t know where to but I expect it will be for Germany but I

wish it was the other way. I am feeling very blue these days as I ain’t feeling

very well. I have got an bad cold & the weather is miserable & I ain’t

had no mail from Scotland for about a month now. I don’t know what is the matter

with them. I ain’t had any from you either for 5 or 6 days but of coarse I have

not been expecting any as I got 4 of yours together the last time. You know it.

Around Manur the villages were so thick you didn’t know when you left

one and entered the next. They ran right into each other and sometimes the men

would march for miles through what seems like one long street and probably pass

half a dozen villages without knowing it.

Every village

was bedecked with flags and streamers across the streets and cards and banners

of welcome in about six different languages. The people cheered and clapped

their hands or wept, as the mood strikes them

KINMEL PARK WALES JAN 1919-MAR1919

On the 27th January

1919 Grandpas was transferred to

England for demobilizing, he was posted to Kinmel Park in Northern Wales to

await his return to Canada

There is a 90-year-old legend in the North Wales town of Bodelwyddan. On some nights you can hear the sound of soldiers marching through the town, but if you look, none can be seen. The soldiers are the spirits of Canadian troops that rest in St. Margaret’s Churchyard in the town. 208 Canadian soldiers are buried there, most of them victims of the influenza epidemic that was rampant in Europe and North America in early 1919. Four of the graves are different: they are the graves of soldiers that were killed when the Canadian soldiers in the Kinmel Park Army camp mutinied in 1919.

For the17,400 troops at Kinmel Park, conditions were far from ideal. The days were filled with exercises that they thought meaningless, medical examinations, route marches and military discipline and training. For them the war was over and they didn’t see the need. They were anxious to return to Canada, not just to their families, but they also realized that the first soldiers home would have the pick of the available jobs, and no one wanted to come home from the war and be unemployed. At Kinmel Park, there was the military bureaucracy to overcome. Troops awaiting transport had to fill in some 30 different forms with approximately 360 questions. The food they were fed was bad; it had been compared to “pigswill”. At night, the troops had access to “Tin Town” a nearby group of shops and pubs that had inflated their prices to take advantage of the, comparatively, well paid Canadian soldier. After a month of these rates, many soldiers were broke. At Kinmel, probably because it was supposed to be a short term camp, the men did not receive regular pay,

Although warmer than most Canadian winters, the winter of 1918-1919 was also one of the coldest that the locals could remember. With the camp situated right on the coast, the men were exposed to the constant, harsh wind that came in off the sea.

In late February it became common knowledge that a number of large ships had been reallocated to the American troops, who hadn’t been overseas for as long as the Canadians. As a last straw, at the beginning of March, General Sir Arthur Currie made a decision to transport the 3rd Infantry as a whole back to Canada, instead of the troops waiting at Kinmel Park, who were originally scheduled for these ships. There was no question that these were combat troops who deserved to return quickly, but they hadn’t been overseas as long as many of the men stationed at Kinmel Park

On 4 and 5 March 1919, Kinmel Park experienced two days of riots in the

It was reported: "The mutineers were our own men, stuck in the mud of North Wales, waiting impatiently to get back to Canada – four months after the end of the war. The 15,000 Canadian troops that concentrated at Kinmel didn't know about the strikes that held up the fuelling ships and which had caused food shortages. The men were on half rations, there was no coal for the stove in the cold grey huts, and they hadn't been paid for over a month. Forty-two had slept in a hut meant for thirty, so they each took turns sleeping on the floor, with one blanket each."

“This resulted in five men being killed and 23 being wounded. Seventy eight men were arrested, of whom 25 were convicted of mutiny and given sentences varying from 90 days' detention to ten years' penal servitude."

On the 22 March 1919 Grandpas finally got to head home. He boarded the “SS Regina” from Liverpool which would take him to Halifax and then a train ride to Medicine Hat to his family.

|

| British War Medal |

|

| Victory Medal |

No comments:

Post a Comment